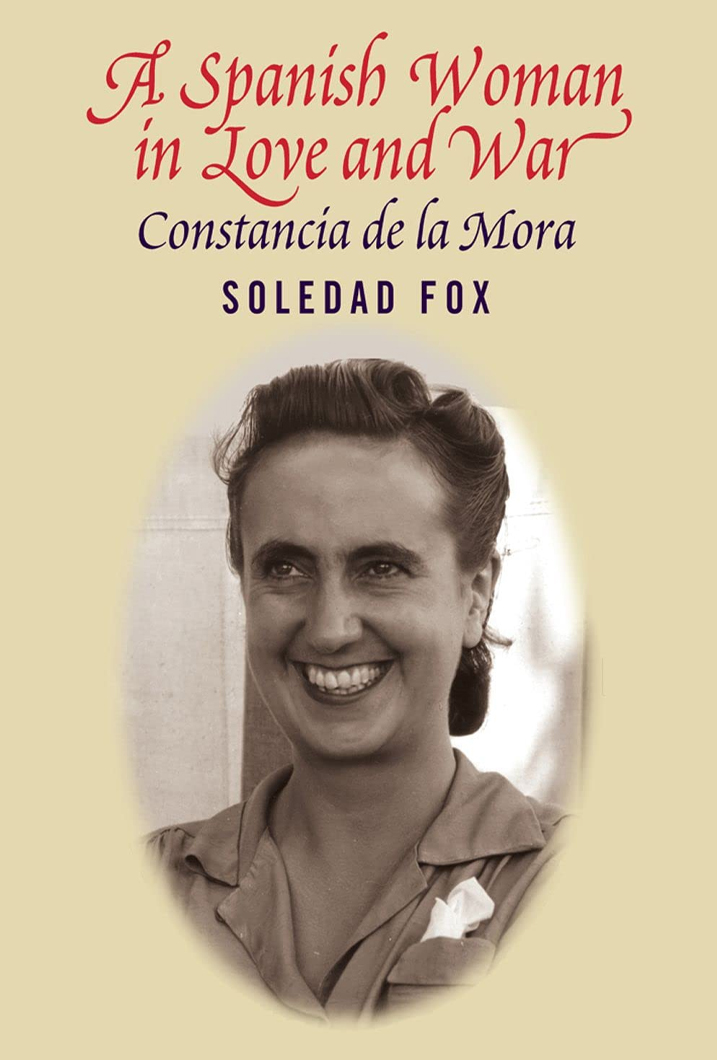

A Spanish Woman in Love and War: Constancia del la Mora

Her fame seemed guaranteed by the compelling story of her life.

She had been an aristocrat turned Communist, a celebrated author, and an international political figure whose acquaintances and collaborators included Stalin, Eleanor Roosevelt, Ernest Hemingway, Tina Modotti, Vittorio Vidali, and Anna Seghers among many others.

Yet, surprisingly, instead of remaining a heroine of the Republic, Constancia de la Mora's memory somehow faded from Republican history. This books sets out to explore the life of this privileged woman who unexpectedly cast in her lot with that of the Spanish people.

TOP REVIEWS

There have been many heroic left- wing female figures during the Spanish Civil War; Dolores Ibarruri (La Pasionaria), Irene Falcon, Marride Campos and Elviria Taborda to name a few. All had fought on the side of Republicanism against Franco, Hitler and Mussolini’s military forces.

Most fought from the idealistic framework of their working class backgrounds. Constancia de la Mora was different. She came from a ‘quasi aristocratic inheritance’ and given the enormous poverty gaps in Spain around the early 20th century ensured that she grew up with some semblance of her own class consciousness of which she ultimately rejected. Constancia was the granddaughter of Antonio Maura, the conservative politician during the reign of King Alfonso XIII; she had access to huge wealth and privilege. However, having married at an early age and then rejecting and subsequently divorcing her husband, when divorce under the strict Spanish Catholic regime was almost unheard of, she entered into a great leap forward in the early 1930’s by embracing the Republic cause and joining the Communist Party to fight the early throes of Fascism.

She wrote a book of her ordeals and life in the civil war titled ‘In Place of Splendour’. She left Spain towards the end of the war, with her only child in Russia; and entered the United States to lobby for the Americans to send aid to Spanish refugees interned in France. She met and socialised with American liberals; amongst those were Eleanor Roosevelt and Ernest Hemingway. She became a great agitator and champion from afar, but was ostracised by her powerful friends in American Government due to her allegiance to the American Communist Party, which at the time took its orders from Moscow. For several years she resided and worked in Mexico before she was tragically killed in car crash, a day before her 45th birthday, in Guatemala in 1950. A brilliant but short life. However, the question I would ask of her if she was still with us today is how does someone from a background of privilege and wealth end up siding with those that are diametrically opposed to her class and ideals.

The author, Soledad Maura researches her facts methodically, files are unearthed from the FBI and the Comintern, unpublished letters, memoirs and photos are brought to surface. There appears to be an unanswered fundamental question as to how and ultimately why De La Mora chose this course of political action; to reject wealth and privilege and side with an ideology that would overthrow the Monarchy and its inheritors at a moments’ notice .How did she become a revolutionary? True, as she developed her political consciousness she could never go back to her so called ‘Aristocratic’ existence; indeed, her family ex-communicated her, and there is some dispute as to whether her family actually ever did belong to a ‘Royal’ lineage.

The reader gets the odd glimpse through the young De La Mora asking questions as to why so many in Spain were in hardship and her family was not. Her family shrug off any of her questions regarding inequality of life in Spain. The author does strongly suggest that the book ‘In Place of Splendour’ was not actually written by De La Mora but by her left-wing American friend Ruth McKenney. Del La Mora did consider herself a writer but many of her friends did not. McKenney had written the acclaimed ‘Industrial Valley ‘ in 1939 and De La Mora’s written English could not have possibly constituted In Place of Splendour. The author writes that McKenney gave her daughter an inscription on the title page of a copy of In Place of Splendour written in 1939 at Westport, Connecticut for Constancia de la Mora.

The fact remains that De La Mora was so strong in her conviction that a better world lay ahead if the Fascists were defeated that you cannot criticise her for her ghost written memoirs. She rejected her background and her family and sought her conviction in Communism as the next world order that would end war, poverty and class distinctions. She was by all accounts a great organiser during the Civil War. Often said to be headstrong, aloof and without a sense of humour.

She was well respected amongst her peers and most were convinced she was a genuine ‘fighter for the cause’ despite her upbringing. The book is fairly short at 177 pages and gives us some detail of De La Mora’s move from the ‘right’ to the ‘left’ in the political spectrum. A very rare thing indeed as most of us choose the other way round as we get older and more dissolutioned with the performance of so called Socialist Governments towards the rampant ideals of Capitalism. Well worth the read.

—Paul O’Connell